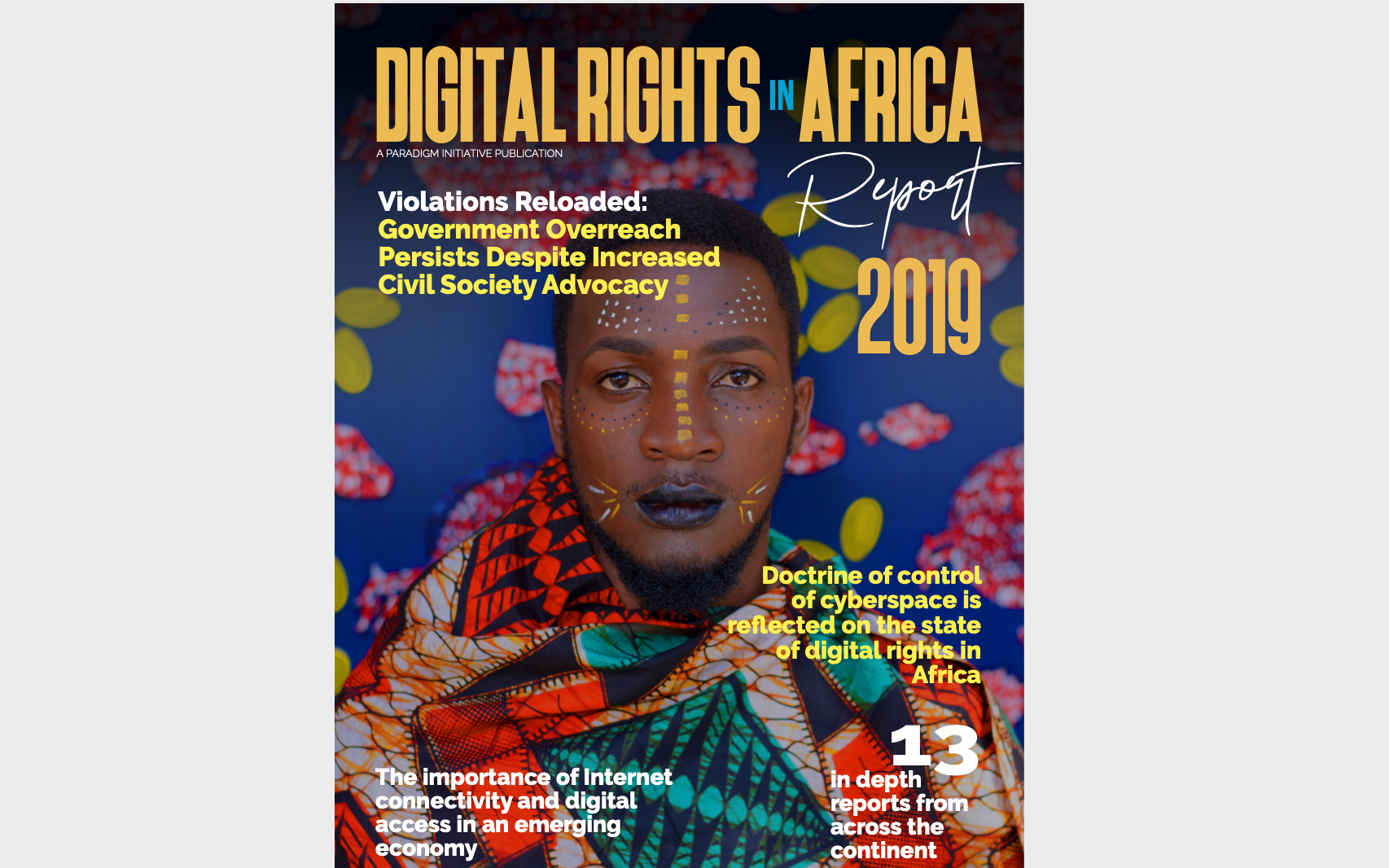

Paradigm Initiative Releases Digital Rights in Africa Report 2019

July 9, 2020

TOR for Consultant to conduct Assessment on Access to Arable Land in Delta, Edo and Ondo States

July 16, 2020

The conflict between State and Non-State actors is an age-old activity on the African continent. According to a 2018 policy brief by the Nordic African Institute, the African continent has in place over 350 peace agreements for the cessation of hostilities, of which 81% are between State and Non-State Actors. Whether it is Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Mali, the Central African Republic, or Nigeria, African countries, aided by their Regional Economic Committees (RECs), such as the International Governmental Authority for Development (IGAD), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the African Union, or other international organizations such as the United Nations, have all often opted for the use of peace agreements as a means to address violent conflicts. However, this reliance on peace agreements has been less than successful.

Why Peace agreements fail in Africa

On the continent of Africa, despite the establishment of 350 peace agreements over the years, real peace tends to be elusive. This is because most peace agreements are not meant to affect structural change or address historical grievances but usually serve as stop-gap measures to stem the bloodshed.

In 1989, when Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPLF) launched a military attack against Liberia in a bid to topple President Samuel Doe’s government, few people would have thought that it would degenerate into a 7-year civil war that took a total of 17 peace agreements before it finally came to an end. Unfortunately, despite the efforts put into these peace agreements, the country descended again into a bitter 4-year conflict that claimed over 300,000 lives and included the use of children as soldiers to prosecute what was largely seen as a war fueled by ethnicity and underpinned by greed. This time, the major parties where the Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) led by Sekou Conneh and the Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL). But the Liberian conflict, like many others on the continent, not only caused internal chaos, but also succeeded in drawing in Liberia’s West African neighbors, setting the stage for other conflicts and internal wars that raged in Sierra Leone, Guinea, and played a role in destabilizing Cote d’Ivoire.

Dirty diesel, petrol, and kerosene; the toxic trio for Nigerians’ lungs and livelihoods

The reliance on peace agreements in African countries is common to every region on the Continent and continues to be the preferred option for the cessation of hostilities. Peace agreements are often facilitated by professionals or mediators who put in months or sometimes years of hard work shuttling between the various interest groups competing for power in some of Africa’s most notorious countries. In some instances these peace agreements have been largely effective in bringing about a temporary cessation of violence through the securing of ceasefire agreements or DDR arrangements, but, in the long term, however, most are ripped apart by the very same actors, often joined by new faces, who begin their agitations once the new balance of power is perceived as unfavorable. Experts have argued that some peace agreements do not address the structural violence and historic social injustices inherent in the society, but merely serve as a stop-gap measure between one war and another, allowing parties to rest and realign, before resuming hostilities. The failure of most peace agreements to address the very structural vulnerabilities and systemic injustices is fed by popular discontent and the perception of yet another failed peace agreement. Unaddressed, these long-held grievances usually fuel a relapse into conflict. Just as in the case of Liberia above, the initial peace agreements did not address the strong ethnic sentiments and perceived injustice suffered by some ethnic groups in the country.

When there is ambiguity regarding the actual objective of the peace agreement, failure of that peace agreement is a certainty, as was the case of the Abidjan Accord of 1996. The civil war in Sierra Leone lasted for 11 years (1991-2002) and was triggered when the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) with support from Special Forces of Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia attacked Sierra Leone with the intention of overthrowing the government of Joseph Momoh and imposing Foday Sankoh, the head of the RUF. Although the Momoh’s government put up resistance against the RUF, it was largely unsuccessful in retraining their devastating march towards Monrovia, the country’s capital, until it was dethroned by a military coup led by Captain Valentine Strasser in 1992. The new National Provisional Ruling Council (NPRC) led by Strasser was also ineffective in stopping the RUF and NPFL assault on the country. The war, which ravaged much of the country’s rural areas, killed more than 20,000 civilians and left hundreds of innocent bystanders maimed and traumatized. It displaced almost 1.5 million people from their homes and livelihoods, orphaned thousands of young children, and imposed financial and social burdens on much of the relatively stable population. A particular heinous tactic of the war, similar to Liberia, was the use of child soldiers, which is in violation of numerous international agreements. In 1996, an attempt was made to reach a peace agreement known as the Abidjan Accord. The accord collapsed within months of signing mainly due to the RUF’s refusal to agree to disarmament and the creation of a monitoring force. In addition, the involvement of private military companies supported by foreign governments meant that the ceasefire was viewed as forced by the RUF and thus illegitimate to many of the fighters.

Ending Cultism in the Niger Delta – Policy Weekly, Vol.2 Issue 20

The Loss of power, or the appearance of a loss of power by one party to another, or the imposition of what may be seen as “outsider demands,” is yet another reason why these peace agreements tend to fail. In the case of Sudan, this was one of the prevailing reasons why the numerous peace agreements reached ultimately failed. Sudan became independent in 1956, but soon after independence, the country entered its first civil war which lasted until 1972 with the signing of the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement. However, peace was temporary and lasted only 11 years before the country was plunged into another civil war in 1983 when the Sudanese government imposed Sharia law on all Sudanese and redrew provincial boundaries, which effectively cut off the South from the oil-rich areas and the fertile lands of the Upper Nile. This second, more violent conflict, which lasted for 22 years (1983-2005), is regarded as one of the longest civil wars on record. The major actors during this deadly conflict were the Sudanese central government and the Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Army (SPLA). The conflict led to the deaths of more than 2 million people and the displacement of almost 4 million people until yet another agreement known as the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (involving 8 protocols) was signed by the parties in 2005. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement led to the independence of South Sudan. One of the reasons the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement failed was the insincerity of the Sudanese Government to fully commit to the full implementation of the agreement, with conditions such as the one-to-one ratio of Southerners to Northerners in the Military and the development of the South.

Perpetuating old mistakes in Nigeria

It’s hard to teach an old dog new tricks, and this may just be the case with Nigeria, as it refuses to learn from the same mistakes made by other countries on the continent. Peace agreements in Nigeria are mainly between the government (Federal or State) and Non-State actors, such as insurgents or armed groups. An analysis of failed peace agreements in the country reveal three major reasons for the failure:

- The Nigerian State utilizes peace agreements when there is a lack of political will to deal with the problems that led to the conflicts in the first place. For almost a decade now, the Nigerian State has been locked in a bitter battle with Boko Haram insurgents. According to the Global Conflict Tracker by the Council on Foreign Relations, since 2011, Boko Haram attacks have led to the deaths of more than 37,000 people and the displacement of 2.5 million people in the Lake Chad Basin. During the first five years of its incursion into the Nigerian space, the insurgents were reported to have evaded the counteroffensive of the Nigerian Military with ease, even controlling large swathes of land and establishing a caliphate. However, a renewed offensive by the military from 2015 has led to the regaining of those lost territories and restricting Boko Haram to specific communities in Borno State. It’s clear now that what’s driving the Boko Haram insurgency is a series of structural social and political issues that have intermingled with an initial economic condition to ensure that marginalized people in Nigeria’s North-East region continue to remain at the fringes of the economic system. In the face of this huge security crisis, the Nigerian State declared an Amnesty for repentant Boko Haram members. While it can be argued that amnesty, in this case, can be a tool for de-radicalizing members of the group that were forced to take part in the group’s activities, the issues such as economic inequalities, poverty, and illiteracy that drove the conflict still remain. For example, Nigeria continues to top the list of the world’s poorest countries with more than 10 million out of school children according to UNICEF.

- The Nigerian State adopts the use of peace agreements as a means solely to buy peace in the short term so as not to deal, pushing the issue further down the field for another administration to deal with. When the Presidential Amnesty Program commenced in 2009 as a gesture of goodwill by the government to appease the Niger Delta militants, few people would have foretold that after 11 years the monthly stipend of NGN65, 000 would still be paid to ex-militants that took up arms against the Federal Government. During the height of the Niger Delta crisis, armed militants under the umbrella of the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), held the country hostage by kidnapping oil workers and mounting a series of attacks on Oil and Gas facilities in Nigeria’s Niger Delta region. Among the grievances of MEND was the need for environmental and economic justice in a region that has produced the bulk of the country’s revenue yet the region is still largely underdeveloped. Many had hoped that the Amnesty Program would be a means to cease hostilities and further development in the region. Unfortunately, that was not to be as the region still largely suffers from the deprivation and marginalization that led to the crisis more than a decade ago. In fact, in 2016, another bout of insurgency commenced, this time taking the name Niger Delta Avengers, with numerous attacks carried out on Oil and Gas facilities across the region. According to the Group Managing Director of the country’s State Oil Company, the Nigerian National Petroleum Company, Nigeria lost more than $4.8 billion dollars in revenue as a result of the 2016 attacks by the Niger Delta Avengers.

FG, others move to re-integrate 30,000 Niger Delta ex-agitators

Conclusion

According to the Nordic Africa Institute, “If peace agreements do not deal with how people are going to live in the future and do not promote ‘positive peace’, they will continue to fail to end suffering and prevent future conflict.” For peace agreements to be successful, they must be used correctly, with the clear understanding that ultimately, peace agreements are a stop-gap measure that provides opportunities for parties to work on the deeper structural, socio-economic, security, and political challenges that drove the violence in the first place. Peace agreements should be followed by other peacebuilding measures such as the establishment of transitional justice measures and community engagement/reconciliation measures at the local level. For instance, instead of focusing on disarmament alone, governments can draw up a reconciliation program to address deep-seated grievances from marginalized groups; instead of focusing peace deals solely on combatants, governments can commit to a pathway for addressing economic and social inequalities at the heart of grievances from marginalized groups; peace agreements can focus on creating more inclusive governance processes rather than replacing one warlord with another.

One fundamental approach to adopt is to refuse to view conflict as the absence of physical violence or war, but rather as the evidence of a struggle against systemic oppression inherent ‘’in a society’s cultural, economic and political structures.” This way, peace agreements can be utilized to address those socio-economic drivers of conflict. This Brookings Institute article aptly captured this point when it stated that “making peace may require compromises on justice. But kicking justice aside entirely prevents peace from taking hold. When impunity reigns and misgovernance, political dysfunction, and serious abuses by powerbrokers go unchecked, the conflict has an all-too-easy path back.”

______________

Nkasi Wodu is a Lawyer, Peacebuilding Manager for the Partnership Initiatives in the Niger Delta (PIND), one of the largest CSR investments in West Africa and the lead facilitator of the Partners for Peace Network (P4P), a network of over 9,000 peace actors in the Niger Delta that establishes grassroots-led community initiatives in order to contribute to the reduction of violence. He holds a Master’s degree in Peace and Conflict Studies and led the development of a robust early warning and early response architecture and the most comprehensive dataset on conflict risk publicly available in Nigeria.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are of the author and not of NDLink

Image Credit: SABC News