EFCC Seeks New Law To Prosecute Contractors Who Abandon Projects in the Niger Delta

August 31, 2018Strategic Implementation Work Plan (SIWP) for Development in the Niger Delta (2017 – 2019)

August 31, 2018The U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals? There’s an App for That.

Entrepreneurs are leveraging technology, including smartphone apps, to accomplish what bureaucracies are incapable of achieving alone.

The U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals, a set of 17 objectives to “end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for all,” ultimately “will be led by countries,” the world body says. But the most innovative ideas for creating clean water, reliable energy, and sustainable fisheries are found as far as one can get from government agencies or U.N. planning bureaucracies. Entrepreneurs using smartphone technology—which is abundant even outside the world’s richest countries—are providing consumers access to information and markets that help them lead more sustainable lives. Something as small as an app is already proving it can deliver in ways that even the power and reach of government bureaucracies cannot.

United Nations officials set the SDGs for 2030, by which time nations are supposed to meet certain metrics to improve energy efficiency, conserve water, and reduce overfishing , among several other aims. The goals themselves are laudable and continue a worldwide trend the past few decades toward more economic prosperity and a cleaner environment. Achieving them, however, will occur only if, as the U.N. puts it, “we manifest these goals in our own lives.”

It is here where innovators are coming through, using the power of smartphones to get the world closer to realizing goals previously thought to be implausible. Entrepreneurs using mobile phone technology are finding ways to tackle the problems identified in the SDGs. While many of these efforts are small, the opportunity and potential for progress are remarkable and apply to a range of targets and countries.

Take, for example, Sustainable Development Goal 6, to provide clean water and sanitation. One of the U.N.’s targets is to “achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all.”

Enter eWATERpay. In Gambia and Tanzania, eWATERpay is installing water taps with smart meters that allow easy payment from mobile phones and a reliable source of income for water companies and encourage conservation.

When you are paying for every drop, your incentive to be careful with your water use greatly increases. Alex Burton, the CEO of eWATERpay, says that there’s evidence in customers’ usage habits. “Water waste is reduced by 99 percent,” Burton says.

Burton notes that about 40 percent of water-delivery points in many developing countries break down within 18 months of installation. “They are broken because the money isn’t collected,” he says. By providing a predictable source of revenue for water taken from a tap, the owners of the water system have an incentive, and the funds, to keep equipment working. “We monitor the system, so when there is a fault it appears on our dashboard and there is an SMS message sent to the repair technician. The time to correct faults has gone down from weeks to hours.”

More than 90 percent of people in Sub-Saharan Africa have mobile phones, meaning most people can access these new taps. It shouldn’t be surprising that eWATERpay was selected as the “Outstanding Mobile Contribution to the UN SDGs” for 2018 at the Mobile World Congress earlier this year.

Technologies like eWATERpay that harness the versatility and ubiquity of mobile phones are quietly beginning to solve some of the world’s most challenging environmental problems. Helping ocean fisheries recover is another opportunity.

By 2030, Sustainable Development Goal 14 seeks to “increase the economic benefits … from the sustainable use of marine resources, including through sustainable management of fisheries.” Sustainable fisheries and economic security go hand-in-hand. Just ask Tim Fitzgerald of the Environmental Defense Fund.

As director of EDF’s Fishery Solutions Center, Fitzgerald served as a judge for this year’s Fishackathon, a worldwide technology competition sponsored by the U.S. State Department, the government of Canada, and the Canadian tech not-for-profit Hackernest. In dozens of cities, computer hackers came together in February to solve challenges proposed by groups like EDF.

Helping fishers become more economically stable was the focus of the challenge proposed by EDF and Fitzgerald. Programmers confronted the problem of providing fishers with information about where they could receive the best price for their catch. Choosing the best port to sell their fish means not only more money, but it reduces the chance that fish will go to waste for want of a buyer.

ALSO READ: Malo: Renewable energy can bridge power generation gap

Sustaining global development goals in Nigeria’s construction industry

Femi Royal: A careful examination of food security issues in Nigeria

“When fishermen plan their business better, they are more likely to engage in new initiatives and programs that are less about catching as much as you can and more about maximizing the value of the fish,” says Fitzgerald. “If all they have ever known is catch as much as you can and sell it for what you can, you can’t have a real sustainability conversation in that environment.”

Finnder, an app developed by the local Fishackathon winners in San Francisco, uses an SMS system that works on a simple flip phone. By providing the latest price information for various fish species and market demand in ports, fishers can be certain they are receiving the best return for their catch.

Improving the finances of fishers won’t completely solve the problems of overfishing ( the global winner of the Fishackathon is attempting to address that issue), but it is a critical part of improving the lives of people and the health of our oceans.

On land, the SDGs make access to “to affordable, reliable, and modern energy services” a prominent goal. “Energy is the golden thread that connects all the Sustainable Development Goals,” notes U.N. Deputy-Secretary-General Amina Mohammed.

Providing that access to remote areas has been a problem in a sector that typically relied on large, capital-intensive projects. How, then, can we create reliable electricity systems for people who do not have access to the capital for such projects?

“The answer is to pay as they go,” notes Luni Libes. The head of Fledge, which he describes as a “conscious company accelerator,” Libes has worked to address this problem with many entrepreneurs he’s helped train.

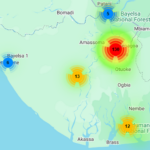

The pay-as-you-go approach, however, means people need to have a reliable means to pay and a way to know how much energy they are using. From Nigeria to Bangladesh, solar mini-grids take advantage of smartphone technologies to allow users to buy and share electricity without the massive capital outlay of standard electrical grids. The European Union and the Green Village Electricity (GVE) Project are building two solar mini grids in Nigeria, capable of producing 100 kilowatts of electricity. The system will include “smart intelligence prepaid meters installed up the poles, which runs on a pay-as-you-go technology, meaning that the communities will use power on a pay-as-you-go basis,” according to GVE’s managing director.

In Bangladesh, SolShare is creating a microgrid that allows people to trade electricity among the solar panels using mobile money. The effort received a $1-million grant from the U.N. Department of Economic and Social Affairs last year.

It may be in developing countries where these opportunities will progress most rapidly. Where government institutions are most established, small-scale technologies have a difficult time conforming to existing regulatory constraints. Although some are attempting to launch minigrids in places like Brooklyn, their biggest challenge is compliance with a heavily regulated sector.

In developing countries, however, those barriers are much smaller. Two decades ago, a lack of institutions was deemed a major obstacle to development. Today, notes economics professor Michael Munger of Duke University, software and smartphones allow countries without those institutions to “leapfrog the usual drawn-out development process and produce useful services.”

Of course, these opportunities exist in developing countries, as well. Toronto-based company Ecobee produces a smart thermostat that uses artificial intelligence to help “double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency,” addressing another of the U.N.’s energy targets. Ecobee is even sharing data from users who volunteer with researchers, to help understand how to make buildings more energy efficient.

For decades, the focus of sustainable development has been the work of the World Bank, governments, and international NGOs. The ubiquity of mobile phones and smartphone technology is now complementing their work and rapidly changing the opportunities to aggregate small improvements that add up to big solutions. The first green shoots of these efforts are already showing.

To their credit, the World Bank, U.N., and others recognize this trend and are supporting many of these efforts, providing grants to energy innovators like SolShare and mobile technologies that support the SDGs, like eWaterpay . The low-overhead costs of smartphone-based approaches, however, means innovators can find solutions even if they don’t have a large, institutional backer. Remarkably, the phone in your hand is emerging as a powerful tool to dramatically improve the environmental and economic sustainability of our planet.

By TODD MYERS, the Director of the Center for the Environment at Washington Policy Center

Culled From – weeklystandard